By Tom Gill

It seems incredible that just a few months after UK farmers were struggling to cope with the endless rain which came with one of the wettest winters on record, many farmers and growers are now talking about drought.

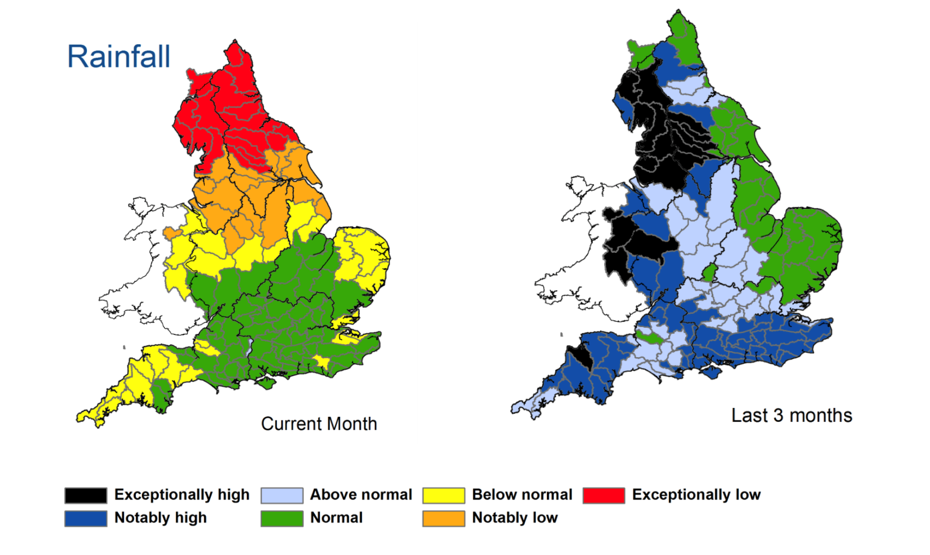

Many areas saw just a few millimetres of rain during April, with England seeing just 50% of its long-term average for the month (the north-east and north-west of the country, in particular, experienced very dry conditions).

The lack of rain at a critical period of the growing season has left many in despair over the British weather, and how to deal with water storages. Many producers are predicting dire results for the coming harvest — a particularly bitter pill to swallow given that the previous three months were so wet (see image below).

For many farmers and growers, prolonged dry spells during the spring and summer growing seasons are unfortunately becoming the norm.

In 2018 farmers had to deal with incredibly challenging conditions after the summer recorded the highest temperatures on record. Meanwhile 2019 saw below average rainfalls for most of the year although an abnormally wet June saw rainfall reach 200% above the month’s usual levels).

At the time, the head of the Environment Agency (EA) made a stark warning about the dry weather trend, saying that within the next 25 years, England won’t have enough water to meet demand.

A quick glance at the EA’s Water Situation Reports and it’s easy to see why. Ground water has steadily declined since the 1970s, and even with the exceptionally wet start to 2020 some aquifers have reported below average levels for this time of year.

With the EA predicting the next three months (May – July 2020) will see below-average rainfalls, alarm bells should be ringing for farmers and growers alike.

Shortage safeguards

Safeguarding farm businesses against long-term water shortages might sound like an impossible feat; after all, no one can control the weather.

But there are things farmers — and everyone in the supply chain — can do.

Water waste, something the head of the EA said should be ‘as socially unacceptable as blowing smoke in the face of a baby’ is an important area most businesses can improve on.

The big question is, how many farms and businesses can honestly say they know how efficiently they use water, as without careful monitoring it’s impossible to tell.

Water sub-metering is an area that many farmers could benefit from, and are particularly useful in individual livestock buildings.

If you’re unsure where to start, then it’s always worth seeking advice. The Promar Sustainability team can map water flows into a farm and advise on where water wastage can be reduced, and where water use efficiencies can be made.

For example, on a livestock business, you can’t change demand, but you can change provision and address leaks and old pipework.

Reduce vulnerability

It’s also essential that farmers take steps to make their land less vulnerable to water shortages.

That means adapting farming practices to improve soil water retention, and looking at management strategies to help alleviate the impact of drought.

This could include considering different cropping choices, which might include introducing drought-resistant crops that can cope with very dry conditions, such as triticale and lucerne.

Meanwhile, building soil organic matter will help with soil moisture retention. Planting cover crops like radish or vetches over winter and ploughing them back in prior to maize drilling will help build organic matter and soil structure.

It’s also worth looking at water capture strategies to see if farm reservoirs or bowsers can be used to create a water buffer during shortages.

And finally efficient water-use technologies, such as on-demand water troughs, could help reduce leakages and other water loss.

Ultimately, the key is around planning and understanding how water can be used more efficiently within a farm business.

If we don’t change our attitudes to water use, then in the future food production could come under even tougher pressures — something most businesses will agree they’ll struggle to cope with.