By Tim Harper

For over half a century we’ve supplied data to UK dairy farmers with both our financial herd costing services; Farm Business Accounts and Milkminder. This ocean of historic data provides us with a barometer of how farmers have responded to past challenges. It also gives us useful insights into how farmers can best respond to the current Covid-19 pandemic and any future major disruptions.

History teaches us that external events outside the control of dairy farmers lead them to make more transformational businesses changes than usual. My view is that Covid-19 will impact dairy farmers less than the introduction of milk quotas in 1984, the deregulation of the Milk Marketing Boards in 1994 or the breakup of Milk Marque in 2000. I also think it will be less disruptive than the removal of milk price support which has all but disappeared as market liberalisation had been adopted by trading blocks. Price paid by processors to producers is more chaotic than ever before, introducing an era of milk price volatility previously unknown.

The Covid-19 impact has more in common with the distress caused by and Foot and Mouth in 1967 and 2001 and extreme weather events, including the very wet summer of 2012, as well as the severe droughts in 1976, 1995 and 2018. These are significant challenges but are generally short lived. They test even the most resilient businesses and tip the weakest ones over the edge.

Farmers are not immune and have to respond to the challenges of Covid-19. However, I believe the global environmental challenges and the demands and opportunities created by Brexit will be far more transformational to them. Much of the response to past challenges has been led by the adoption of technology. Genetics, animal health, forage and feeding technology have played a big part in the past. More recently, robotic milking and the widespread use of sexed semen have added to the arsenal of innovation widely embraced by farmers. We expect digital technology combining robotics, sensors and data analytics using artificial intelligence to become more widely adopted on farms in the next decade.

Whatever technology is chosen, it will be used to support increased output at lower cost. If it doesn’t, it is hard to understand why it will succeed.

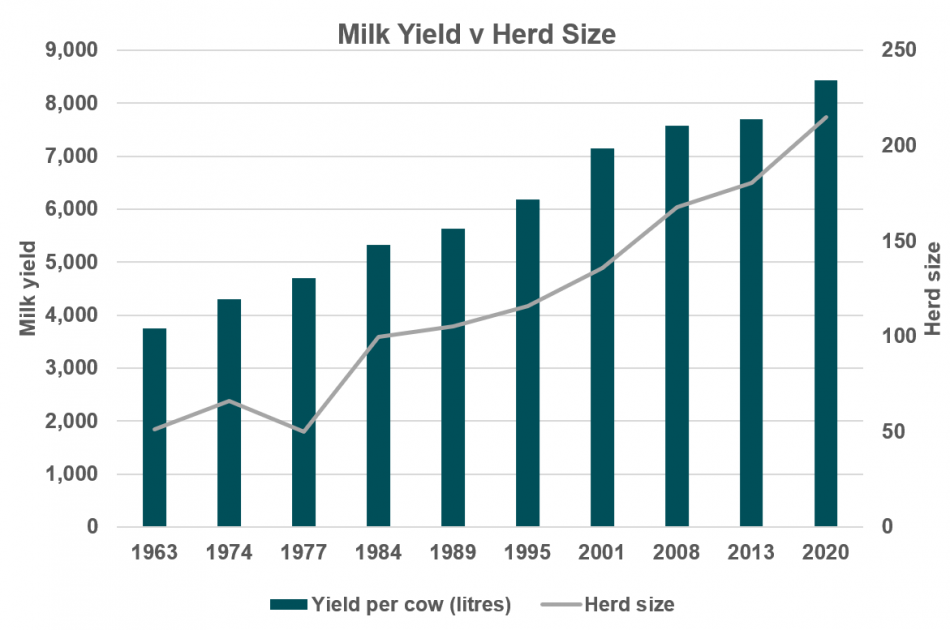

The graph below shows how milk yield and herd size have risen during the last 57 years.

The average milk output of the farms shown has grown by nearly tenfold, yet the total number of herds has dropped dramatically. Over this period, total UK milk output has increased by around 40% although it’s been relatively stable since the introduction of milk quotas in 1984.

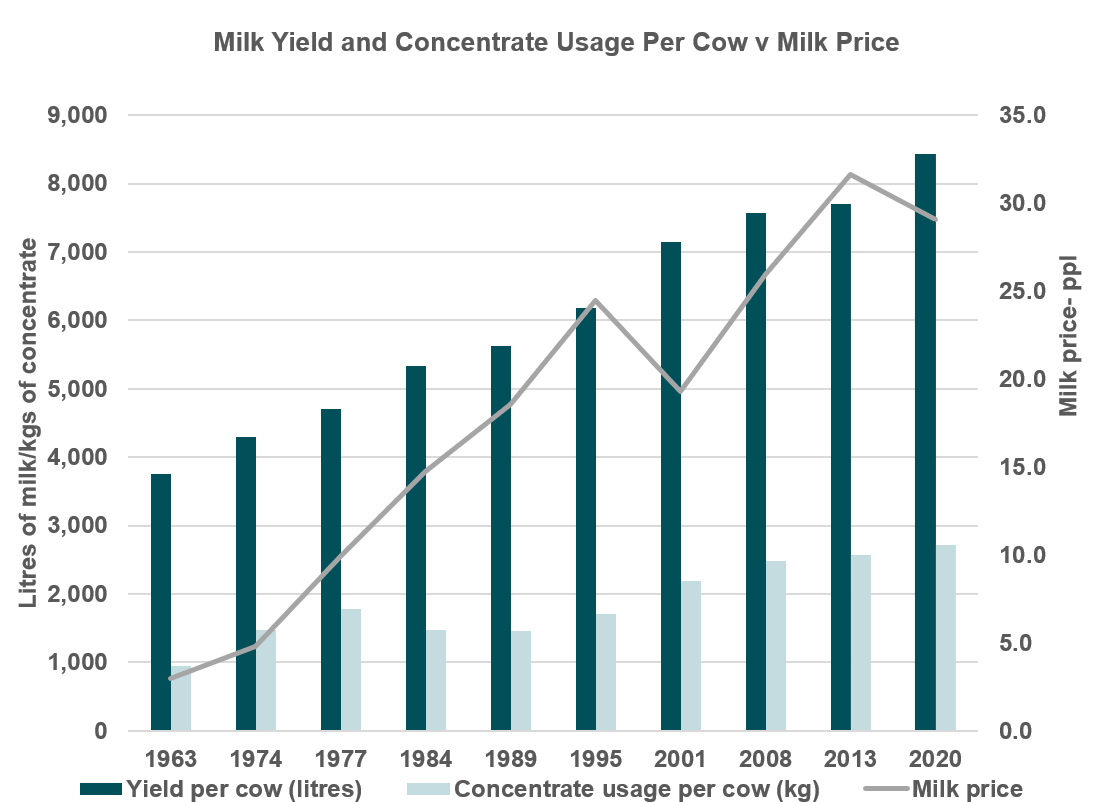

This next graph summarises the average milk yield and concentrate usage when compared to milk price from our long-standing farms from FBA and Milkminder.

Milk price inflation has averaged around 4% during this period, compared to an average inflation rate of around 5.5%. The rate of milk yields increase has averaged just over 2% per annum compared to concentrate usage which has increased by just over 3% per annum, meaning that average feed rate has increased from 0.25 to 0.32 kg/litre. One notable year on the graph was 1984 when the introduction of milk quotas led to big falls in concentrate usage, but milk yields still increased. In contrast the 2012 wet summer led to milk yields being suppressed leading to a rise in feed rates.

Moving forward it is likely that herd size will increase, and the rate of genetic gain will accelerate providing greater opportunities to increase milk yield from the same level of concentrate, or to cut concentrate levels while maintaining milk yield. History would suggest that most farms will pursue higher yields. However, with increasing demands from consumers around producing milk more sustainably, there will be an opportunity to produce milk with a lower ecological footprint.

In spite of the significant challenges the industry has faced in the past, our data illustrates the resilience of UK producers who adapt to ensure a heathy industry over the long term. But we know success isn’t easy or guaranteed and blind optimism is not a good recipe for success. It’s good to learn from history and use this knowledge to develop a strategy and plan for the future.

There will be a vast array of new innovations offered to farmers; some will work well, and others won’t. One thing is certain, more data will be generated and more ways to analyse it will be created. At Promar, our position will always be to ensure there is a clear and beneficial link between herd output and profitability and we will develop our tools and analysis with this as a core goal.

If you are interested in any other historic data analysis, we would be happy to help. Alternatively, if you would like some help and advice on getting through current challenges then please contact us.