By Emma Stuart

Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis (IBR) is a hidden disease in many dairy and beef herds, but one that is proving to be costly. Within the UK, it is present on around 60% of farms, costing the industry an estimated £36 million annually. On an individual scale, if IBR becomes established in a herd, it is estimated to cost around £82 per cow per year in lost production and infertility. Looking at these figures, it has become vital that farms recognise the signs of this highly infectious disease and how it can be eradicated before it becomes the Covid-19 of the cattle world.

So, what is IBR and where does it come from?

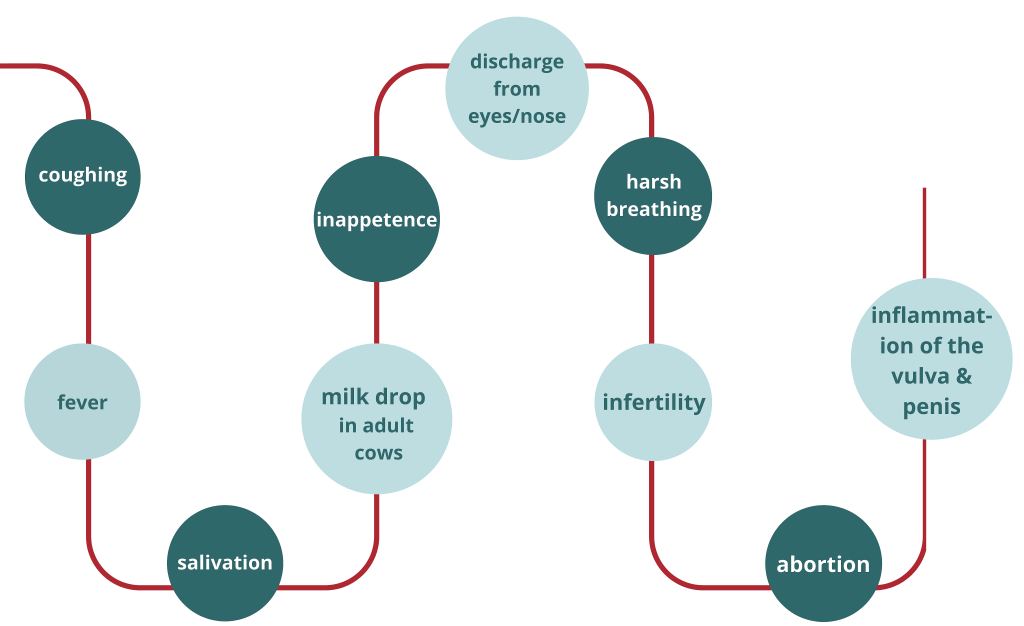

IBR is caused by bovine herpesvirus and can cause a range of symptoms, but most commonly respiratory signs (see Figure 1). Unfortunately, it can show similar signs to other diseases such as BVD/Mucosal Disease to Malignant Catarrhal Fever and other causes of pneumonia, making it extremely important to get a veterinary diagnosis when symptoms are present.

Cattle of all ages are at risk of the disease, but it is typically found where different ages of youngstock are mixed together in groups. It should also be noted that herd purchasing animals with an unknown IBR status are also susceptible.

The virus is shed in huge quantities in nasal and ocular secretions, saliva, cough particles and even in semen. It can be transmitted across short distances (up to 5m) but can also be carried on clothes, footwear and equipment, thus hygiene is of utmost importance.

There are four main methods for diagnosing herd outbreaks

- Nasal or conjunctival swabs

- Broncho-alveolar or tracheal lavage (BAL)

- Blood tests to check for antibodies – this option can only be considered once the outbreak has established, as it can take about two weeks for the animals to mount a detectable immune response.

- Bulk milk testing is also common in dairy herds, but the results should be interpreted with caution. A negative result does not completely rule out IBR, as a significant proportion of the herd must be infected before the test shows up as positive.

Eradicating IBR

Once an animal becomes infected with the IBR virus, they are infected for life. This means that they become a carrier, showing no clinical signs. During stressful periods, however, they can resume shedding of the virus and could potentially infect other vulnerable animals. This is why immediate steps need to be put in place towards removing positive animals from others.

While eradication in herds with established IBR can be time-consuming and costly, it is desirable for several reasons. One being that it can perpetuate other causes of pneumonia such as Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), Parainfluenza (PI3), BVD, Mannheimia haemolytica and Mycoplasma to name but a few.

The key to avoiding IBR incursion onto your farm is adherence to good farm biosecurity, isolation and testing of purchased animals, erecting adequate fencing to avoid nose-to-nose contact with neighbouring animals, and ensuring bulls have been tested for the virus before use. Vaccination is also a mainstay of control, but given the different protocols available, it is important to discuss and review your policy with your vet regularly to ensure you are following it correctly.

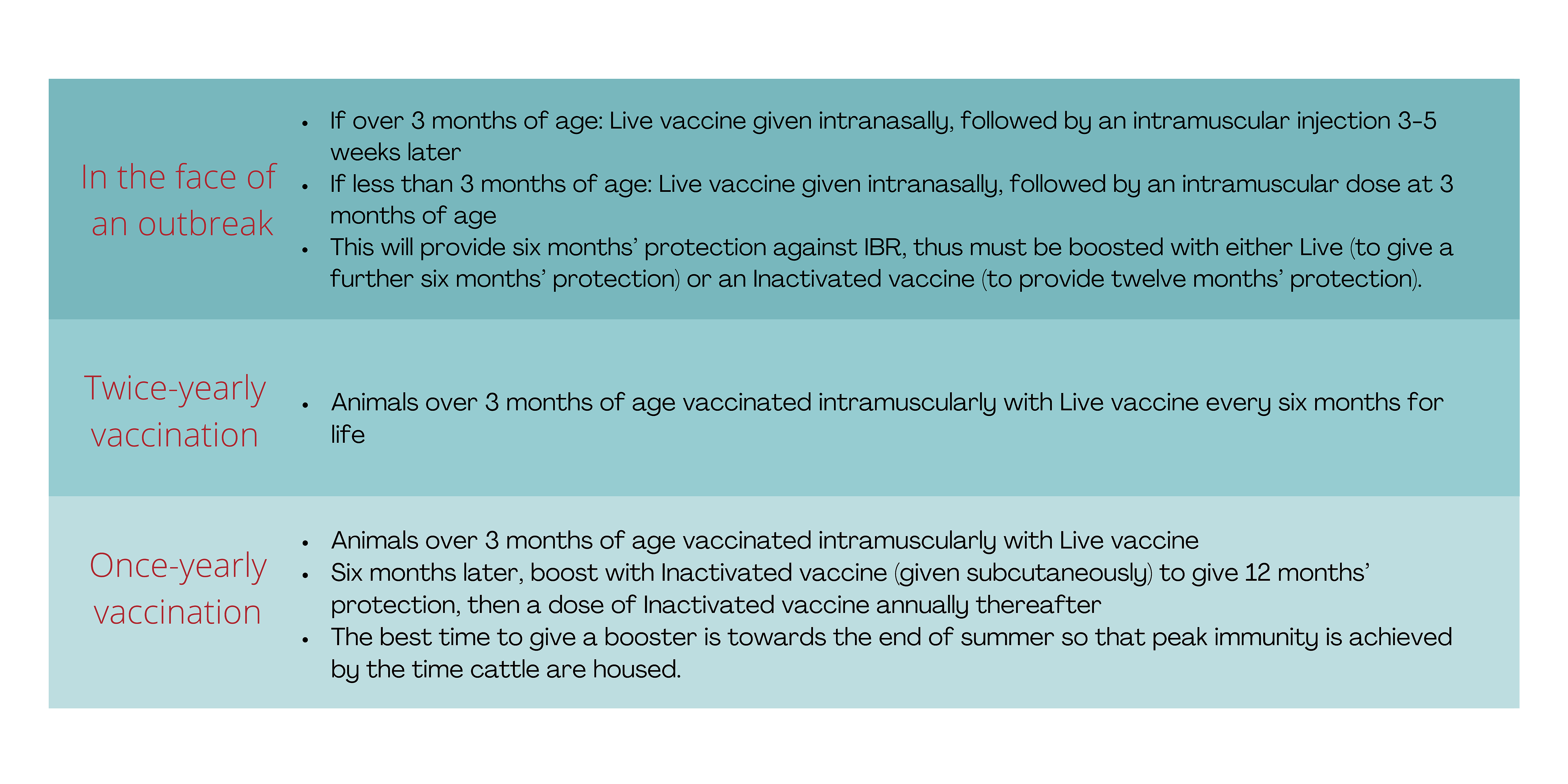

Two main vaccination protocols are used, ‘Live’ and ‘Inactivated’. Live vaccines are most suitable for use where animals are at immediate risk of IBR or in herds where IBR is not endemic. Inactivated vaccines are most suitable for reducing the shedding of virus by latently infected carrier animals in infected herds.

The message at this stage is; be aware, understand and appreciate IBR control. It is an increasingly common disease, and it’s becoming more evident that you need to be mindful of your IBR status. We’re here to help you with this process and to offer guidance on diagnosis and vaccinations.